Lewis J. Stadlen is one of those legendary entertainers of Broadway, film, television and the international cultural sphere, whom it is simply impossible to forget for his over four decades delighting audiences of all ages. It may well be possible that most remember him for the first season of the sitcom “Benson,” in which he co-starred alongside Robert Guillaume, James Noble and Inga Swenson, but those truly in the know will equally remember his sensational work as Groucho in the 1970 cult Broadway musical hit Minnie’s Boys, with star Shelley Winters and fellow Marx Brothers Danny Fortus, Irwin Pearl and Alvin Kupperman. Later, he would portray Groucho again in a critically-acclaimed national stage tour, and fall into the hearts and minds of legions of fans. Before, after, in the meantime and in between, he would create the part of Ben Silverman in the original company of Neil Simon’s The Sunshine Boys, receive a Tony nomination for being Pangloss in the 1974 production of Candide, portray Lupinski in Mel Brooks’ 1982 celluloid remake of the classic film To Be Or Not to Be, play a featured role in Neil Simon’s The New Odd Couple in 1985 (which starred Rita Moreno and Sally Struthers, along with Stadlen and budding newcomer Tony Shalhoub as the male Latino love interests from upstairs), and find himself at this writing back on Broadway in Douglas Carter Beane’s play The Nance at the Lyceum, with Nathan Lane. Stadlen may not have picked up a heavily-deserved and unfairly-ignored Tony nomination in the process, but he remains one of the finest thespians of the last forty-plus years; the son of renowned voice-over artist Allen Swift always seems to roll with the punches regardless of the trappings of awards and tinsel. He’s even published a memoir, Acting Foolish, available at Amazon. And The Andrew Martin Report couldn’t be more thrilled that he took time out of his schedule to grant us an interview.

Lewis J. Stadlen is one of those legendary entertainers of Broadway, film, television and the international cultural sphere, whom it is simply impossible to forget for his over four decades delighting audiences of all ages. It may well be possible that most remember him for the first season of the sitcom “Benson,” in which he co-starred alongside Robert Guillaume, James Noble and Inga Swenson, but those truly in the know will equally remember his sensational work as Groucho in the 1970 cult Broadway musical hit Minnie’s Boys, with star Shelley Winters and fellow Marx Brothers Danny Fortus, Irwin Pearl and Alvin Kupperman. Later, he would portray Groucho again in a critically-acclaimed national stage tour, and fall into the hearts and minds of legions of fans. Before, after, in the meantime and in between, he would create the part of Ben Silverman in the original company of Neil Simon’s The Sunshine Boys, receive a Tony nomination for being Pangloss in the 1974 production of Candide, portray Lupinski in Mel Brooks’ 1982 celluloid remake of the classic film To Be Or Not to Be, play a featured role in Neil Simon’s The New Odd Couple in 1985 (which starred Rita Moreno and Sally Struthers, along with Stadlen and budding newcomer Tony Shalhoub as the male Latino love interests from upstairs), and find himself at this writing back on Broadway in Douglas Carter Beane’s play The Nance at the Lyceum, with Nathan Lane. Stadlen may not have picked up a heavily-deserved and unfairly-ignored Tony nomination in the process, but he remains one of the finest thespians of the last forty-plus years; the son of renowned voice-over artist Allen Swift always seems to roll with the punches regardless of the trappings of awards and tinsel. He’s even published a memoir, Acting Foolish, available at Amazon. And The Andrew Martin Report couldn’t be more thrilled that he took time out of his schedule to grant us an interview.

ANDREW MARTIN: If your father hadn’t been Allen Swift, do you think you would have followed a career path into acting regardless? And what was it like having him as a dad? Can you discuss your childhood?

LEWIS J. STADLEN: There is, of course no way to know. It was my mother who discovered a theater camp, Gray Gables Theatrical Workshop, in Kitchawan, New York, for me to attend when I was fourteen. She sensed I had a creative bent. It was the first time that I felt self-confident about anything. I made my acting debut as Petrovin the artist, in a remarkable teenage production of Anastasia (Marta Heflin played the title role). My chief motivation, which continues to this day, was that girls took a greater interest in me. I attended the camp for two summers, and my social life revolved around a Saturday dance class during the school year that was attended by many of the campers at the wonderfully-atmospheric rehearsal studio, Variety Arts, across the street from the Forty-Sixth Street Theater. The Gray Gables Choreographer, Joe Vilane, who to this day is the best choreographer I have worked with apart from Agnes DeMille, taught the class. So because of that experience, I glimpsed the possibility of leading a useful life. That said: I was extremely insecure about everything, and without my father’s unending knowledge and support, and the future rejection I was to later experience in the “real” grown up world, I’m certain my early enthusiasm would have been nipped in the bud. He was instrumental in every way in helping me to navigate the minefields of an exceptionally cruel and capricious business. He was instrumental in my ability to land my first job, which was the first national company of Fiddler On The Roof when I was nineteen. By that time, I had had the good fortune of NOT being invited back to the Neighborhood Playhouse, owing to the presence of one of the all time sadistic- bastards Sanford Meisner, who was probably responsible for destroying the confidence of thousands of talented, but all-too-trusting and self-critical souls. It was the first major rejection I experienced and with the help of my father, I was able to overcome it and by chance fall into the nurturing embrace of the great Stella Adler, who actually taught me the fundamentals of my craft which I use to this very day. As I review a career that is into it’s forty-seventh year, I realize I’ve mostly learned my survival skills from my actor-father, while my over all sense of choice and sense of esthetics have been gleamed from my college-professor mother, Vivienne Schwartz. I would not have survived in my profession without either of their support.

AM: What are your thoughts about Minnie’s Boys, both the fact that you were so young to make your Broadway debut and also playing Groucho? (We’ll come back to the Groucho factor later). And was it surprising that even though the show retains a cult status, it really didn’t run very long? Also, what was it like to work with Shelley Winters?

LJS: Well, cult status is highly subjective. It’s rarely revived because the libretto is terrible, and as absurd as the creative experience turned out to be, I can only be grateful for what turned out to be my entree into the theatrical community. I no longer had to introduce myself. (Be careful what you wish for.) There were many reasons why Minnie’s Boys failed. Shelley Winters was a disaster, but mostly, the story was thought to be in the same vein as Gypsy. But Gypsy was not about Gypsy Rose Lee’s attainment of fame as much as it was the story of her ambitious stage mother. Rose was a very human monster, and the show’s conflict had to do with the effects her behavior had on her children. Minnie’s Boys was about a show business family, devoid of any conflict. Everyone loved Minnie, and it was hardly a mystery as to whether the Marx Brothers would eventually overcome the obstacles before them and become a success. The original director and choreographer were two of the most inept individuals I have encountered in my forty-six years in Show Business; the choreographer is, ironically, a member of the Theater Hall Of Fame, which is a credit to her political abilities and certainly not her talent. Shelley Winters, a terrific film actress, was completely over her head in a musical comedy. You will observe that in most of her film performances she is usually murdered by her leading men, be it drowned, choked, stabbed, run over by a bus, etc. She was one of those performers who had the ability to throw her weight around, thinking only of herself, but in this case she did not possess the requisite skills to selfishly get what she wanted and wound up thoroughly subverting herself and the entire project. She was actually fired in previews, but her contract was such that the producer’s could not afford to pay her off for a year and hire another star performer. One being Kaye Ballard, who I performed with in a subsequent production at Pittsburgh’s Civic Light Opera in 1972. She was wonderful, but the role had already been cast in stone due to Shelley’s many deficiencies. As for the show running for some eighty performances in previews and another eighty after we opened, everyone wanted to bend over backwards to make it a success with the exception of the critics. It just wasn’t good enough, even though it possessed a mostly-winning score and had some excellent performances. As they say, “The fish stinks from the head down.” That said, it was one of the most meaningful experiences of my life, and Danny Fortus (Harpo), Irwin Pearl (Chico) and Alvin Kupperman (Zeppo) remained friends from that day on.

AM: What were your thoughts on being cast to create the role of Ben in The Sunshine Boys? Was anything particularly intimidating (be it creating a role in a play by Neil Simon, working with Jack Albertson or Sam Levene, etc)?

LJS: It was very intimidating being cast in The Sunshine Boys. For the first few days of rehearsal, I was certain I’d be fired. I was a twenty-five year old actor with limited acting chops. The person who most intimidated me was our director Alan Arkin, who I more than admired. A strange, brilliantly talented man whom I felt I rubbed the wrong way. Neil Simon, who I got to know a great deal better during the next three decades, was at the top of his form in 1972. (I have since done three more of his plays from scratch.) A brilliant artist and craftsman, who I’ve come to realize always brought an operatic element to the productions of all his plays. He suffered not only from fear of failure, but also from success anxiety. A combustible combination. Jack Albertson was a wonderful actor, and it was a pleasure to perform with him. His Willie Clark is still the best performance in that role. But, the person who had the most lasting influence was the GREAT Sam Levene, who to this day I consider one of my foremost mentors, although he would probably cringe at that description. Besides being a great actor, he was incapable of dissembling in an industry that encourages an interactive fraudulence that erodes your soul. He taught me much about onstage comportment, consistency of performance and how to survive in life with your sense of integrity and self-worth intact. For a time, I felt I was actually turning into Sam Levene, who did have a propensity for falling on his own sword. Hopefully, I have taken all that was true in the man and learned to suffer not quite as much.

AM: What was it like to do Candide, and how did you feel about the Tony nomination?

LJS: Candide was, unfortunately, an unhappy experience. I did not get on with Hal Prince, and I don’t care to elaborate as to the reasons why. Let me take some responsibilities for my own actions; I was only twenty-seven at the time, and felt I had to be the spokesman for everyone’s discontent as well as my own. Perhaps I hadn’t quite perfected the good Sam Levene within myself. Based on some very legitimate contractual grievances with Mister Prince, I made the naive mistake of taking him on as a peer, and was crushed in the exchange. At this stage of my short career I believed that doing a Broadway show a year was my birthright, which proved to be a ridiculous assessment. That I could not enjoy the experience is unfortunate, since I have been told by many people that the production itself, and my performance in it, was one of their most enjoyable theatergoing experiences. As for my Tony nomination, the cast was done no favors by Mister Prince, who would not allow any of the Tony voters to come to individual performances. Instead he scheduled a ninth, a Sunday evening performance for all the voters to sit in judgement. We were all nervous and exhausted and, as it turned out, Candide won a flock of Tony Awards, but none for the actors who were nominated from the show. It was par for the course of how the cast was presented, as if we were street urchins turned magically-professional by Hal Prince’s brilliant direction. (He DID win the Tony that year). The experience was instructive in many ways; I lost to the great Christopher Plummer, who probably shouldn’t have won for his performance in the musical Cyrano, but to lose to an actor of such brilliance was an honor in its own right.

AM: We all know that you took a little break from Broadway to play the featured role of Taylor in the first season of the sitcom “Benson.” First of all, what was your experience of that? Secondly, what led to your separation from the show, and was it very harsh? Similarly, did you know that Rene Auberjonois would be replacing Taylor with his own character of Clayton? How did that feel?

LJS: “Benson” was the epiphany needed to figure out what I wanted from my profession. My dear Stella Adler had posed a question to our acting class years before, whether our priority was to become an ACTOR or a STAR? I thought the question daft. Obviously, a star would get the opportunity to play the best parts. Why wouldn’t one aspire to stardom? “Benson” allowed me to fully appreciate the distinction. It was a thoroughly loathsome experience. Even when one is engaged in a poorly conceived theatrical endeavor, there is some flicker of idealism that one might be creating something of worth. Commercial television is about selling beer and cornflakes; the entertainment exists to serve the product. Everybody in charge of bringing “Benson” into the public sphere lied about everything. Our two crass producer’s were thrilled that the show wasn’t in the top ten in the Nielsen ratings because we had “no place to go but down.” Every week we were told to go out and beat the pants off of “Rudolph the Red-nosed Reindeer.” I didn’t sign my contract until the fifth show, I hated the character I played, and was petrified I’d be typecast as the same sniveling asshole who was only around to be the butt of the joke. Apparently, Rene Auberjonois had no such concern. He was only hired to replace me after I had screamed my way off the show. I remember one of the producers telling me that they would let me out at the end of the season as long as I didn’t expect to get paid in return. He simply couldn’t conceive that I wanted no part of his money. Several months later, I was performing a one-nighter of my two person Groucho show in Mansfield, Ohio. A rather slow young man, who was running the spotlight, approached me at a Ham & Egg just before the performance. “Do you mean to tell me that you would rather be here in Mansfield than in Hollywood doing Benson?” In a flash,I recognized the significance of his question. “YES!” was my immediate reply. And if you notice, I don’t even list my television credits in my Playbill bios. Ever.

AM: In 1982, you were more or less rediscovered by the public by your portrayal of Dr. Gruber in The Verdict. Can you describe that experience?

LJS: It was a terrific experience. Sidney Lumet was a great director and it was an honor to work with Paul Newman, and be a part of the same project as James Mason, Charlotte Rampling and Jack Warden. We rehearsed the film for two weeks at 890 Broadway, as if it were a play. We’d run through the screenplay twice a day. In my scene with Paul Newman, I had ninety percent of the dialogue. It would be a three-minute tracking shot when we filmed it up in Boston, but for the process of rehearsing, Sidney had us walking around the rehearsal studio with me taking the lead and Paul trying to catch up. Because I was in awe of Paul, I’d slow up so I could be face-to-face while we conversed. Sidney kept telling me that he wanted Paul to chase after me because I was a big-shot doctor and his character was a down-in-the-heels lawyer, a drunk. But I kept slowing up due to my respect for Paul, until Sidney took me aside and said, “Listen, you’re fucking a twenty-two-year-old intern across the river in Cambridge. You’ve got three hours to get to her apartment, and then back to Boston before your next operation.” From that moment on, I walked very fast. Giving an actor an “active” motivation is the mark of a great director.

AM: In 1983, the public at large once again got to enjoy your gift of comedy when you portrayed Lupinski in To Be Or Not To Be. What was it like to work with Mel Brooks and company? Were there any standout moments? In particular, what was it like to do the Shylock monologue?

LJS: It was very difficult. Mel Brooks can be a delightful, always hilarious man when he is feeling secure about a project’s prospect for success. In the case of To Be Or Not To Be, he knew he was competing with the original film, which in my estimation is a comic masterpiece. The director of the original, Ernst Lubitsch, was a genius, and Jack Benny and Carole Lombard were brilliant in their respective roles. Because Mel was afraid, and rightfully so, to be compared to Lubitsch and Benny, he pretended that we was not the director of the film. (He was.) Instead, he gave the directing credit to the film’s choreographer, Alan Johnson. This created a dysfunctional working relationship that was very hard on the actors. Mel was especially hard on my interpretation of the Shylock speech, which was a work-in-progress until we finally shot it, seven weeks into the shoot. A large part of being a good director is instilling an actor with confidence, and Mel did the opposite. In retrospect, I realize that Mel was as petrified of performing Shakespeare as I was. The night before the scene was to be shot, I smoked a little grass and came to the conclusion that Lupinski’s motivation had to do with kicking ass for the Jews. But the next day, what I didn’t realize, was that the shot before had me rushing out of the theater men’s room straight at Mel, who was dressed as Hitler, while surrounded by several big, strong, blond body guards in SS uniforms who grabbed me by my arms and hurt me. Suddenly, I wasn’t just emoting Shakespeare’s prose, I was fighting for my life. It was a terrific acting lesson. It’s never about the words; it’s about the subtext you create underneath. Mel was more then pleased, thank God, because you don’t want to get on his bad side! Essentially, with the exception of my rendering of that speech, I was too young for the part. Felix Bressart, who was in the original, was much better. As was everything else in the original film. There was to be plenty more Mel Brooks in my life, but two decades later.

AM: It’s absolutely amazing to think that when the The New Odd Couple came to Broadway in ’85 at the Broadhurst, with an all-female cast featuring Rita Moreno, Sally Struthers, Marilyn Cooper and Jenny O’Hara among others, you played one of the Latino love interests along with Tony Shalhoub, who was making his Broadway debut at the time. What was that situation like in general, first of all with the ladies as the leads and secondly to be working with Shalhoub?

LJS: It turned out to be a turning point. I was thirty-seven, and in a depression over what to do with the rest of my life. I think it’s becoming clearer after the re-telling of these experiences that an actor’s life is not a walk in the park. It’s a roller coaster ride complicated by the need to re-invent yourself every decade, as you morph from flavor of the month,to being a character actor who now appears too young for the roles he might be considered right for. If you’re lucky. The original roles of the Costazuela Brothers (the male re-imagining of the Pigeon Sisters), was written for two middle-aged bald Hispanic actors, and I wasn’t bald, Hispanic or middle-aged. The only reason I was asked to audition for the part was, because as desperate as I was to find work, I had invited the show’s casting director to a Mets game the night before. Having nothing to offer me, she threw me a bone and scheduled an audition the next day for a role I wasn’t remotely right for. That afternoon I found myself in a room with about twenty middle-aged, bald Hispanic actors wondering what the hell I was doing there. I even expressed that sentiment aloud to the actors in the room. One of my many complaints that I voiced at the time was that Raul Julia, who spoke with a decided Spanish accent, seemed to be immune from type. He had recently been cast in Noel Coward’s comedy-drama Design For Living, playing an Englishman with a decided Spanish inflection. Seconds before I was to go into audition for the director, Danny Simon (Neil Simon’s older brother), I decided that if Raul Julia could play Noel Coward, I could play Raul Julia. So that’s what I did. It was a wicked take-off , and it proved hilarious to the powers that be. The next day, I was asked to audition for Neil and I turned the audition down as a waste of time. Some poor bastard had already been cast in the role of the other brother, and there was no way I could appear to be his brother. I received a conference call between the producer Manny Azenberg and Danny Simon that morning, begging me to come down to the Alvin Theater and audition for Neil. The moment I auditioned with the bald, Hispanic actor cast in the other role, I knew I was going to get the part, and that the other actor was screwed. (I never found out what happened to him. He must have been bought out). Neil came down the aisle of the theater, and asked me if I was “fucking nuts” for turning down the audition. When I mentioned the plethora of bald jokes, he told me he would rewrite the part. I was astonished that I had gotten the role, and saddened that it had come off the back of the other actor. But…that’s show business! The moment I walked out of the stage door of the Alvin (which has since been renamed the Neil Simon), a pigeon shit all over my new suit. A woman passing by assured me it was a sign of good luck and I told her I hoped so. After I was cast in the role of Manolo, Tony Shalhoub came in and blew them away as Jesus. It was his first high-profile role, in what has turned out to be an elegant career. Neil Simon rewrote the roles so that the two of us were sexually appealing, and the build up to our characters was so artfully written, that the moment we appeared in the doorway midway through the second act, carrying roses and boxes of candy, the audience was in hysterics. We had great chemistry together. Unfortunately, I got a bit distracted by falling in love with Rita Moreno. But that’s a story for a different time.

AM: How did you come to play Groucho later Off-Broadway and on tour? Was it as a direct result of Minnie’s Boys, or were you just sort of “that Groucho guy?”

LJS: I didn’t play Groucho Off-Broadway. After Minnie’s Boys, I was offered all the plays and sitcoms that had a Groucho character. While Groucho was alive, I was the only actor he allowed to play him. I was super-sensitive about being typecast as his imitator, and tried everything in my power to choose roles as far away from that image as possible. In the 1970s, during a serious lull in my career, I put together a two-character play which I produced, Groucho, which I co-wrote with Denny Martin Flinn, who directed. We performed it for four weeks at the Ford’s Theater in Washington, and three weeks at the Tower in Houston, and were courted by several Broadway producers who wanted to bring it to Broadway. I refused for reasons I listed above, preferring to play one-nighters and split weeks all over the country for three months a year, from 1979 to 1982. I loved playing Groucho Marx, and the show we wrote was funny and literate, but I was happy to do it out of the New York public eye.

AM: You had a relatively-small but absolutely-memorable role on “The Sopranos.” What was that experience like?

LJS: My time on “The Sopranos” was very nice. It was a show I actually watched religiously. James Gandolfini was a remarkably generous actor to work with. The shooting schedule was more like a movie than a TV show; everyone involved seemed aware that this was the greatest gig of their lives. They actually wrote a segment about my character that I couldn’t do because it was the first week I was performing as Max Bialystock on Broadway in The Producers. They just renamed the character and got another actor.

AM: So many people, myself included, feel a regrettable loss from the cancellation of “Smash,” in which you’ve had a recurring role. Can you possibly share what the experience has been like, and why you think it’s hasn’t been able to hang on?

LJS: I watched the first twenty minutes of the first episode I was in and turned it off. I thought it was pretty bad. They wanted me to return for a fourth episode, but I turned them down. When you’re a recurring character, your time is not your own. You’re at their disposal at all times, and I don’t choose to live my life that way. Also, to be perfectly honest, I have memorized books of dialogue in my time, but for some reason I have a hell of time keeping disposable dialogue in my head. When you’re doing a recurring role, you’re usually the last person to be put on camera. Instead of knowing what you’re doing and why, you’re trying to remember the verb that connects the sentence. I am in the fortunate position of not having to take every job that comes down the pike, which is mostly due to my three unions and their generous pension plans. Tell that to those asshole Republican governors from Wisconsin, Ohio and beyond.

AM: How are things going with The Nance?

LJS: I love doing The Nance. It’s a wonderfully ambitious piece. Nathan is his usual brilliant self. Jack O’Brien is a terrific director. The cast is made up of kind and accomplished actors. The Lyceum is my favorite theater that I’ve played on Broadway. That said, it’s exhausting. I used to poo-pooh actors who complained about doing eight performances a week. That I’m jumping around out there like a teenager out there–I can almost see their point.

AM: Finally and honestly, Lewis, where do you see yourself ten years from now?

LJS: That’s a good question. I’ll be seventy-six. Hopefully, I’ll be dining at the Edison coffee shop between a matinee and evening performance of a new play. Along with my old friends (and I MEAN old), Chip Zien, Mark Blum and Lee Wilkof (in their respective shows). With my ten-year-old grandson and Mary Macleod at my side.

Well, hopefully most of us will also all be around to meet them there for a good ol’ Edison corned beef on rye and a coffee. Until then, we’ll all continue to enjoy Lewis J. Stadlen on and off stages and screens, and wish him continued great good luck.

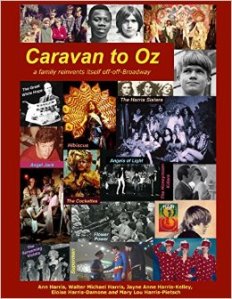

Anyone who has ever availed themselves of the Off-Off-Broadway experience in New York City, whether as a performer, a crew member or simply “one of those little people out there in the dark,” will truly sink their literary teeth into Caravan to Oz, a splendid history of one family’s journey into a most exciting period in the American theater in the Big Apple. Anyone who hasn’t ever availed themselves of the Off-Off-Broadway experience in New York City, whether as a performer, a crew member or simply “one of those little people out there in the dark,” will truly sink their literary teeth into the book all the same. And in any case, this two-hundred-and-seventy page tome laden with stunning photography, emerges as a wondrous history lesson even to those not necessarily theater-oriented. To be succinct, it’s nearly impossible to put down once begun reading. The book bears vague similarities to Edie, the smash recounting of Warhol superstar Edie Sedgwick, except that in this case the story is actually told by the subjects in question, along with additional input by such legends of the Off-Off-Broadway scene and the cultural world at large as Tim Robbins, Bob Heide, Robert Patrick, Crystal Field, Mike Figgis, Mark Lancaster, Ritsaert ten Cate, and the late Ellen Stewart.

Anyone who has ever availed themselves of the Off-Off-Broadway experience in New York City, whether as a performer, a crew member or simply “one of those little people out there in the dark,” will truly sink their literary teeth into Caravan to Oz, a splendid history of one family’s journey into a most exciting period in the American theater in the Big Apple. Anyone who hasn’t ever availed themselves of the Off-Off-Broadway experience in New York City, whether as a performer, a crew member or simply “one of those little people out there in the dark,” will truly sink their literary teeth into the book all the same. And in any case, this two-hundred-and-seventy page tome laden with stunning photography, emerges as a wondrous history lesson even to those not necessarily theater-oriented. To be succinct, it’s nearly impossible to put down once begun reading. The book bears vague similarities to Edie, the smash recounting of Warhol superstar Edie Sedgwick, except that in this case the story is actually told by the subjects in question, along with additional input by such legends of the Off-Off-Broadway scene and the cultural world at large as Tim Robbins, Bob Heide, Robert Patrick, Crystal Field, Mike Figgis, Mark Lancaster, Ritsaert ten Cate, and the late Ellen Stewart.